2020 playlist:

The winter long

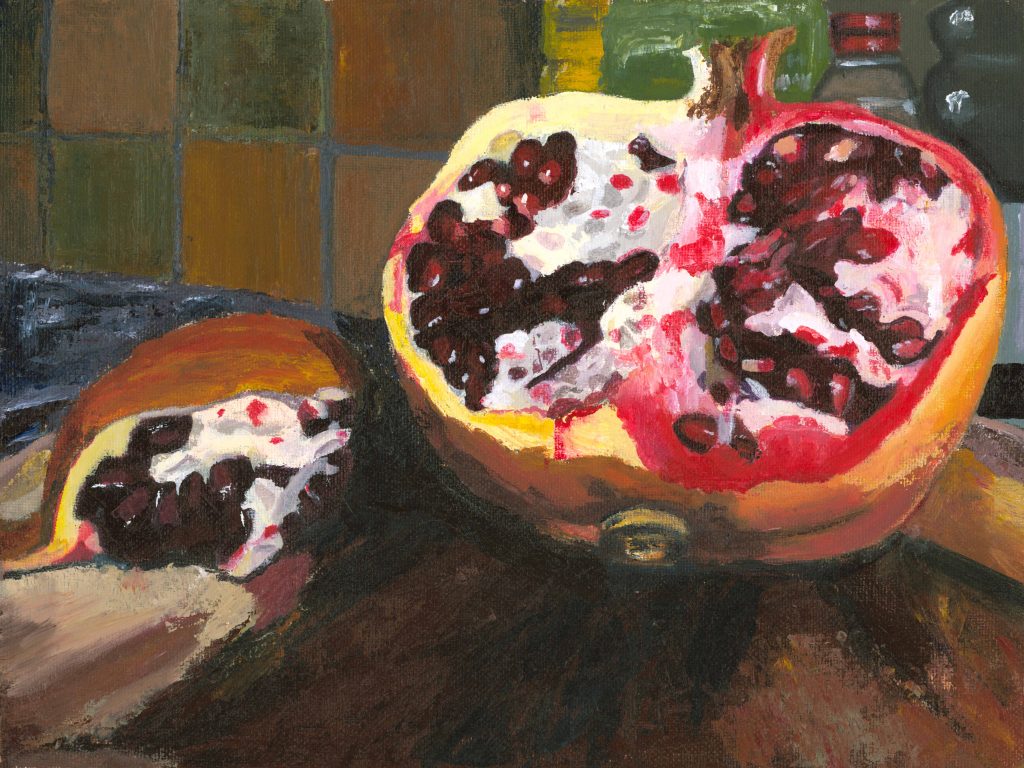

This picture mostly hangs on the wall at the foot of the stairs, so I see it a dozen times a day at least. I painted it seven or eight years ago as a technical exercise – most of the paint is applied with a palette knife, with just a bit of brushwork to work up the highlights on the fruit. It worked well, and came together quickly, with that fast hit of satisfaction you get when you work in a flow state and things fall into place just right, with a clear end point that lets you stand back and say ‘right, that’s done’.

Art History will give you reams of papers on still life and its symbolisms; and pomegranates, having appeared in art since well before the Romans, have accrued a whole host of meanings: beauty and death, fertility and virtue. But this is figurative work, an actual fruit in my actual kitchen, against the background of tiles I disliked when we moved in, and am no keener on fifteen years later.

Now, though, it makes me think of Persephone, roaming Hades waiting for Spring. I can’t paint. Although I need to and the lack of it hurts me, the whole process seems futile, a waste of materials and time. I look at this painting and remember the ease and conviction and I wonder when – if – I will feel that way again.

This is how it works

There is a drinking game we used to play, in tan-bricked pubs with washable floors and on coffee tables piled with ashtrays and takeaway containers. You pull a paper napkin tight across the top of a glass, balance a small coin on it, and take turns to burn holes in the paper with a cigarette. If the coin falls through on your turn, you lose.

Peering into the vortex of world events streaming through the internet, that’s what it feels like we are doing now on a much bigger scale, singeing safety nets one after the other, eating away at the surface we exist on until gravity has enough, resolute in the delusion that it will be someone else that takes the fall. At the same time, we are close to solving more and more problems – it’s our species USP, after all, if you can draw a veil over how many of them we have caused in the first place – but something is still very clearly wrong when anyone on the planet who isn’t an eight-year-old can suggest that a robot army is a good idea.

Having all the necessary knowledge acquired through history on dealing with epidemics (rule one is ‘close your borders’) and having ignored it anyway, we seem to be stuck in a weird mixed economy of forbidding huge tracts of everyday – often instinctive – human behaviors, and carrying right along with things that we already knew were probably a bad idea. Cognitive dissonance, but for entire nations; a whole species.

A few miles from here, the local authority just green-lit yet another logistics centre. Yes, it was a shame about the Roman site, but some archeologists could probably have a couple of weeks to dig through it before the concrete slabs were poured. Bit of a pity about the biodiversity and habitat loss which would definitely happen, but the developer would give money that would make other biodiversity (magically?) appear somewhere else, so that would be fine. Or even if it wasn’t, the priority was the economic benefit to the area ( a couple of hundred low-skill, low-pay dead end warehouse jobs and a few IT and manager roles, that might even survive the looming recession).

Static

By now, I have pretty much ground to a halt. There is another set of prints to finish, but the weather has been cold and damp and out in the plastic conservatory where I work the ink on the last set is still not dry, ten days after printing. There is no room for another set. The most useful thing I can do about paintings is work out where I’m going to put the stack that has been sat out there all summer, somewhere dry where they won’t warp or mold before the spring.

Working from home goes on, and is busy; stuttering rapid-fire barrages of emails and video calls burred with distortion, issues without context. The kids go to school and we try and act as though it’s normal, that every little sniff and sneeze don’t make us remember all over again that them doing so has expanded our circle of contacts from ten people to three thousand. The experience of one of their friends, who spent two weeks on a ventilator and two months in the hospital, and now faces life-changing damage to his heart – at seventeen – makes a mockery of all the brisk, don’t-make-a-fuss statistics.

In my head, just white noise, inertia; stale, recycled ideas that I can scrape up no enthusiasm for. For a day or two I wondered vaguely if I might write here about the work of Abraham Maslow – but then I listened to a podcast that did a better job than I ever could [link here], so that was that. I’m trying – and have been for months – to help somehow, deliver groceries, cook meals, walk dogs; but everywhere I ask I get no answer.

Giving it away

A billionaire has just finished giving away his fortune. It has taken him thirty-eight years to funnel seven or eight billion dollars through charities and foundations. Just thinking about the paperwork that must have been involved inflames my carpel tunnels.

It was a gritted-teeth attempt at a good-news story in a swirling hell-stew of political hysteria, social breakdown and distanced Strictly. At first I thought ‘what took you so long?’, but it must be quite a difficult thing to do without falling foul of hundreds of international laws, laying yourself open to lawsuits, corruption charges, scams and graft. And of course even easier to end up visiting disaster on the people you are trying to help: benefit sanctions, tax bills, robbery with violence.

But committed to the job, unable to understand why anyone would want to sit on a pile of gold and watch the world burn, he hired a team, set up a foundation, and funded healthcare, education and social programmes across the world, at first anonymously, later outed by a legal dispute. Although some kind of charity foundation legacy after you’re dead is pretty standard for the wealthy, the idea of shedding wealth while alive was treated by most as massively eccentric. But he encouraged his fellow billionaires to give it a try, saying ‘it’s a lot more fun to give while you live than give while you’re dead.’

So now this work, which has taken much much longer that making the money in the first place, is done, and he can at last retire. He’s 83.